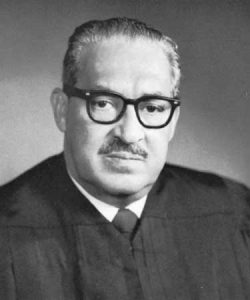

Thurgood Marshall was known to be a gentleman, unfailingly polite and slow to ruffle feathers. While never shrinking from the duty of candor, he maintained that reputation throughout the legal battles of the Civil Rights Movement, his service at the Justice Department and his tenure on the Supreme Court. But if he retained any tact in 1987, at 78 years of age, he dispensed with it in a speech on the Constitution’s bicentennial. Speaking May 6th at a legal conference in Hawaii, Justice Marshall derided the arch-patriots waving their flags in celebration of a constitution that no longer existed:

Like many anniversary celebrations, the plan for 1987 takes particular events and holds them up as the source of all the very best that has followed. Patriotic feelings will surely swell, prompting proud proclamations of the wisdom, foresight, and sense of justice shared by the Framers and reflected in a written document now yellowed with age. This is unfortunate — not the patriotism itself, but the tendency for the celebration to oversimplify and overlook the many other events that have been instrumental to our achievements as a nation. The focus of this celebration invites a complacent belief that the vision of those who debated and compromised in Philadelphia yielded the ‘more perfect Union’ it is said we now enjoy.

Ouch. Recently retired Chief Justice Burger had spent years leading the presidential commission created to celebrate the bicentennial, and Justice Marshall’s comments were aimed squarely at the commission’s work. But he was just warming up:

I cannot accept this invitation, for I do not believe that the meaning of the Constitution was forever ‘fixed’ at the Philadelphia Convention. Nor do I find the wisdom, foresight, and sense of justice exhibited by the Framers particularly profound. To the contrary, the government they devised was defective from the start, requiring several amendments, a civil war, and momentous social transformation to attain the system of constitutional government, and its respect for the individual freedoms and human rights, we hold as fundamental today. When contemporary Americans cite ‘The Constitution,’ they invoke a concept that is vastly different from what the Framers barely began to construct two centuries ago.

Justice Marshall saw two federal constitutions, and the potential for others. He said the first, in 1787, was fundamentally flawed by racism and its accommodations to slavery. It took a Civil War to — in his view — replace it with a better one. That war proved and was a consequence of the original constitution’s failure. The new and improved constitution birthed by the war included a Fourteenth Amendment guaranteeing due process under law on an equal basis to all citizens. The country looked much different in 1987 than it ever could have under that first constitution. He continued:

What is striking is the role legal principles have played throughout America’s history in determining the condition of Negroes. They were enslaved by law, emancipated by law, disenfranchised and segregated by law; and, finally, they have begun to win equality by law. Along the way, new constitutional principles have emerged to meet the challenges of a changing society. The progress has been dramatic, and it will continue. The men who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 could not have envisioned these changes. They could not have imagined, nor would they have accepted, that the document they were drafting would one day be construed by a Supreme Court to which had been appointed a woman and the descendent of an African slave. ‘We the People’ no longer enslave, but the credit does not belong to the Framers. It belongs to those who refused to acquiesce in outdated notions of ‘liberty,’ ‘justice,’ and ‘equality,’ and who strived to better them.

Justice Marshall went on to slay all excuses for the original constitution’s accommodations to slavery. Mainstream commentators were apoplectic, of course. The conventional wisdom was (and is) that the founders’ failure to end slavery was a “compromise” to the formation of the Union. But as brilliantly explained two years later by a Louisiana State law professor, Thurgood Marshall was right (pdf). The only compromises made by those meeting in Philadelphia — Northern as well as Southern — were to their own self-interests.

Former White House official Cass Sunstein, who clerked for Justice Marshall in the late 1970s, recently noted that the debates over whether the founders ever envisioned a right of women to control reproduction, or of gay people to marry, should include Thurgood Marshall’s view of a living, evolving constitution. Clearly, there were many things those old men meeting in Philadelphia couldn’t see, and we are fortunate to have moved beyond their limited collective vision. As we celebrate this year’s Black History Month and the contributions of leaders like Thurgood Marshall, let’s recognize the work that remains on the road to liberty. And let’s pray it doesn’t take another war to build the constitution this country deserves.