The jury has been chosen. Pretrial motions have been decided. Opening arguments start tomorrow. Does your trial planning start now? Last-minute preparation is not uncommon for experienced trial lawyers. For some, it’s a daily routine. But when you’re representing yourself, you’ve got a sleepless night ahead. Is your opening argument too long? Too short? Should you practice more? Were all your witness subpoenas properly served? Will your key witnesses stick to the facts and avoid unnecessary or confusing comments? Will they hold up under cross examination? Are your exhibits too complex? Will the jury misunderstand them or ignore them completely? Will the opposing lawyer object to them? In what order should you present your witnesses? What are the most important facts to elicit from each witness, and how can you make those facts stick when the jury begins deliberating?

So many questions. So many decisions still to be made. So much at stake. Thing is, the biggest factors in your success at trial have already been decided. The most important decisions have already been made. The table has already been set. If trial planning begins for you at this point, you’ve already lost. Which claims and defenses have been dismissed or struck or decided on summary judgment? Which claims remain to be proven and disproven? What evidence did you collect or get forced to hand over in discovery? What evidence has been admitted or suppressed? Which witnesses are allowed to testify, and on what matters? On the eve of trial, the court has already ruled on these issues. And now you must try your case within the limits of those rulings.

How do you maximize your chance of success? Easy peasy, by preparing to win on these issues long before the eve of trial. You should envision the eve of trial at the very beginning of your case, and every step along the way.

Your preparation should start at the end and work backward. Imagine the ideal circumstances on the eve of trial, and figure out what it takes to get there. Here’s the way I think about it. Let’s say you’re defending a debt collection case. What does the trial look like in your wildest dreams? Ideally, trial never happens because you either got the claim dismissed with prejudice or won a summary judgment or settled the case early.

Failing that, the lawyer gets the trial date wrong and never shows, and the court dismisses the case. Or the bank’s records custodian gets confused by all your questions and runs screaming from the witness stand. Or someone hacks the court’s computer system and scrubs your case and all its records. Or… Right, let’s wake up just a little. More likely, you’re able to show at trial that the bank kept sloppy records or lost the original loan contract. Or the records custodian can’t authenticate the loan documents or the transaction report. Or the numbers don’t add up to what’s claimed when you do the math. That’s a good day at trial, because if the bank doesn’t have their case together, they can’t prove you’re liable and they’ll lose. And unless the judge does something stupid and gets your judgment reversed on appeal, there’s no do-over. So how do you get there?

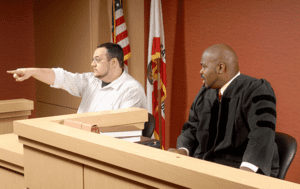

You have a witness — a bank employee — who can testify to the bank’s loan processing and collection practices, and you’ve subpoenaed him for trial. You’ve prepared questions to use in examining your witness, and questions you’ll use to cross-examine the bank’s witnesses. You have exhibits, maybe a Powerpoint file with documents and captions, ready to display on the courtroom’s big screen. You’ve demanded and paid to impanel a jury of your peers. Your motion in limine was successful, so you got your witnesses and exhibits admitted and the bank’s most damaging evidence suppressed. It was successful because your discovery was well planned.

On your motion, the court compelled the bank to produce the documents and other evidence you requested. You fought the bank’s discovery when they sought your tax returns, credit reports and other irrelevant financial data. You were able to object to their more outlandish requests because you’d filed an aggressive motion to dismiss that sharply limited their claims. And you’d fought off their attempt to strike your defenses, so they didn’t dare move for summary judgment against you.

You’d been a quick study on legal research, civil procedure and the evidence code as soon as you were served with the complaint. You spent many late nights finding the elements of the bank’s claims and mapping your facts to several viable defenses. Indeed, some your facts suggested the bank had caused you harm. You’d filed a solid answer with affirmative defenses and counterclaims, effectively turning the tables and putting the bank on trial.

Your trial planning began with a vision of the perfect trial and judgment for you in the end. So now, on the eve of trial, you’re prepared for battle. You remind yourself you’ve been ready for months, since before you filed your answer, because you took time early on to see yourself winning at trial and plot your steps toward that victory. So get a good night’s sleep. You’ve got a busy day tomorrow.